In early summer in Beijing, stepping into the compact yet tranquil space of the Goethe-Institut, Germany’s offical cultural center, the winter and strong winds of Fushun almost pierced through me instantly.

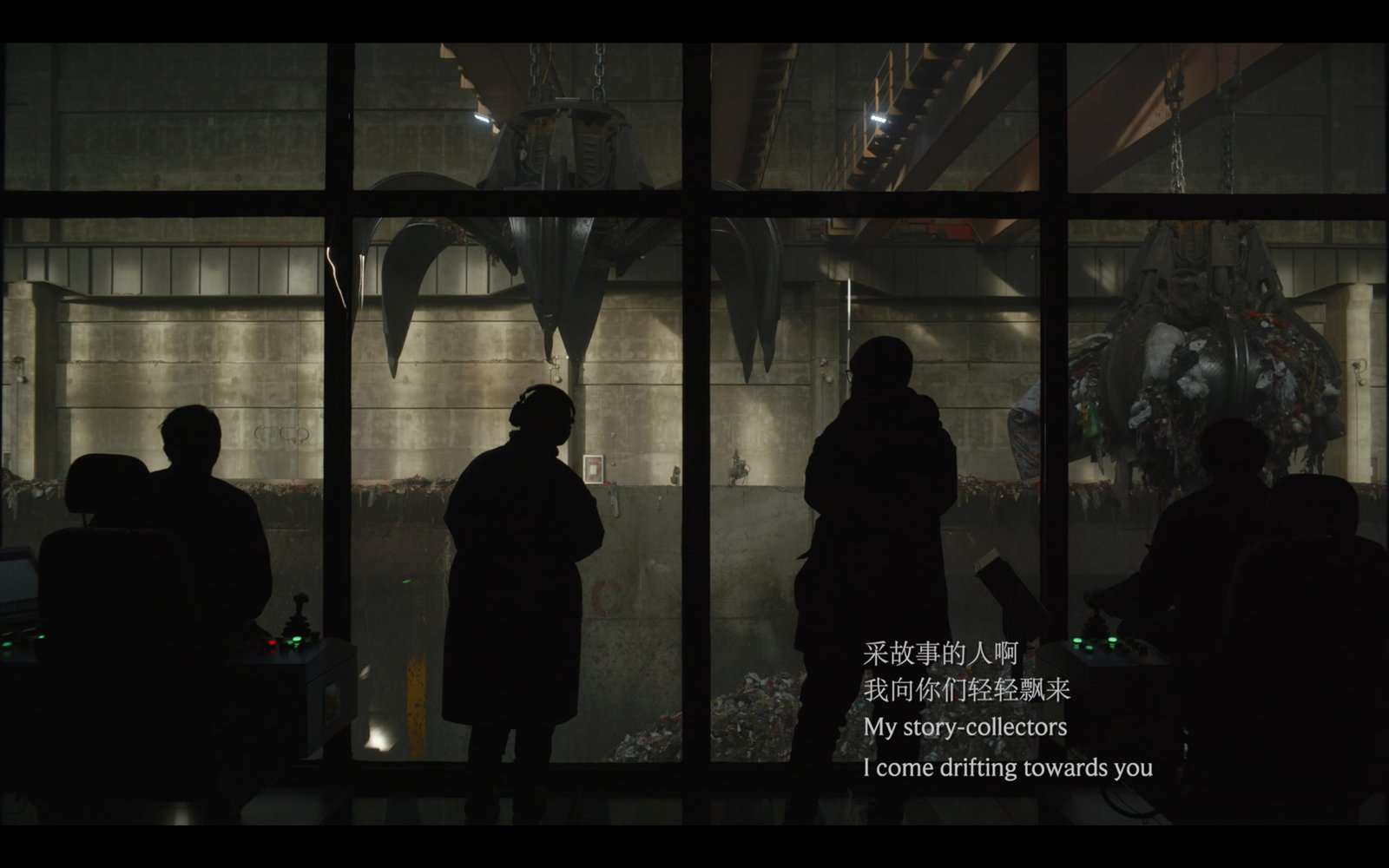

As the door closed behind us, I felt as if I had fallen into a completely unfamiliar universe. The first thing that hit me was the sound: the great roar of industrial spaces, the sharp whistling of machines in operation, the slow storytelling of Mother Earth… Three entirely different frequencies of vibration entangled with each other and wrestled into a strange and incompatible posture, ultimately forming a contradictory and thought-provoking concerto in the tension of camera language.

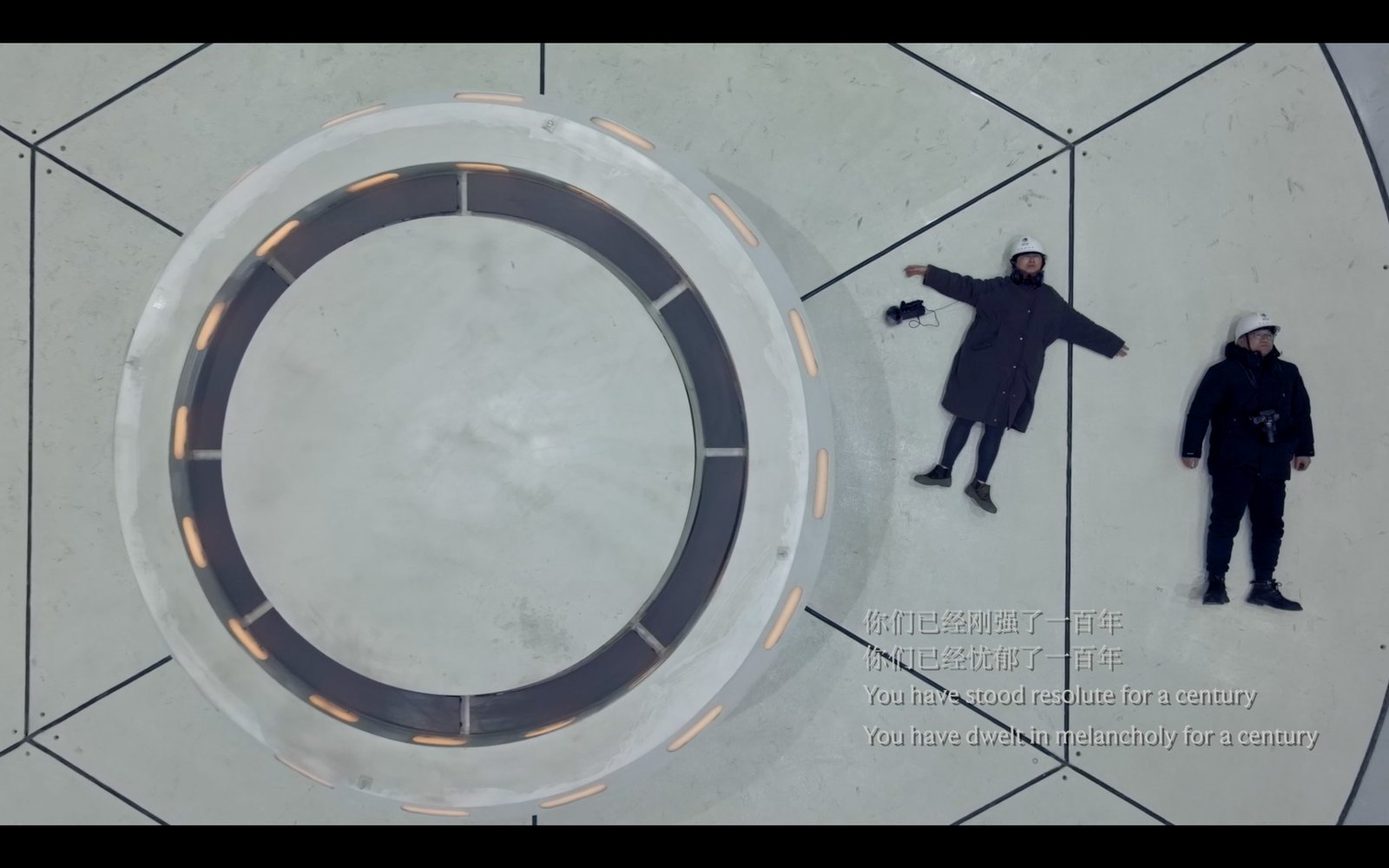

In this 20-minute film, “Emu Universe,” Yu Miao, as both curator and creator, transforms a drone into the eyes of the shamanic legend Emu. Silently, it watches as two “story collectors” curiously intrude. They witness the scars and fractures of Mother Earth, wandering through her hollowed-out body and womb (the exposed mines and ruins). They appear increasingly heavyhearted and uneasy, until Emu finally decides to speak and sing.

At the end of the film, Emu’s voice is calm as ever, speaking not only to the two “story collectors” but to the entire Northeast: “You have been strong for a hundred years, you have been melancholic for a hundred years; shed this strength, shed this melancholy…” At that moment, a strange healing energy emerged from the screen and permeated the exhibition hall. The wounds and pains of the earth, the fading and return of nature, and the confusion and doubt of human beings finally merged under an de-anthropocentric perspective into a kind of almost ubiquitous whispering chant.

Why did a woman, a daughter of the Northeast who hurriedly left her hometown at 18 to wander around the globe, return to the Northeast after all these years? And why did she choose and face Fushun—a place of industrial legacy, but also the crossroad and knot of history and political burdens?

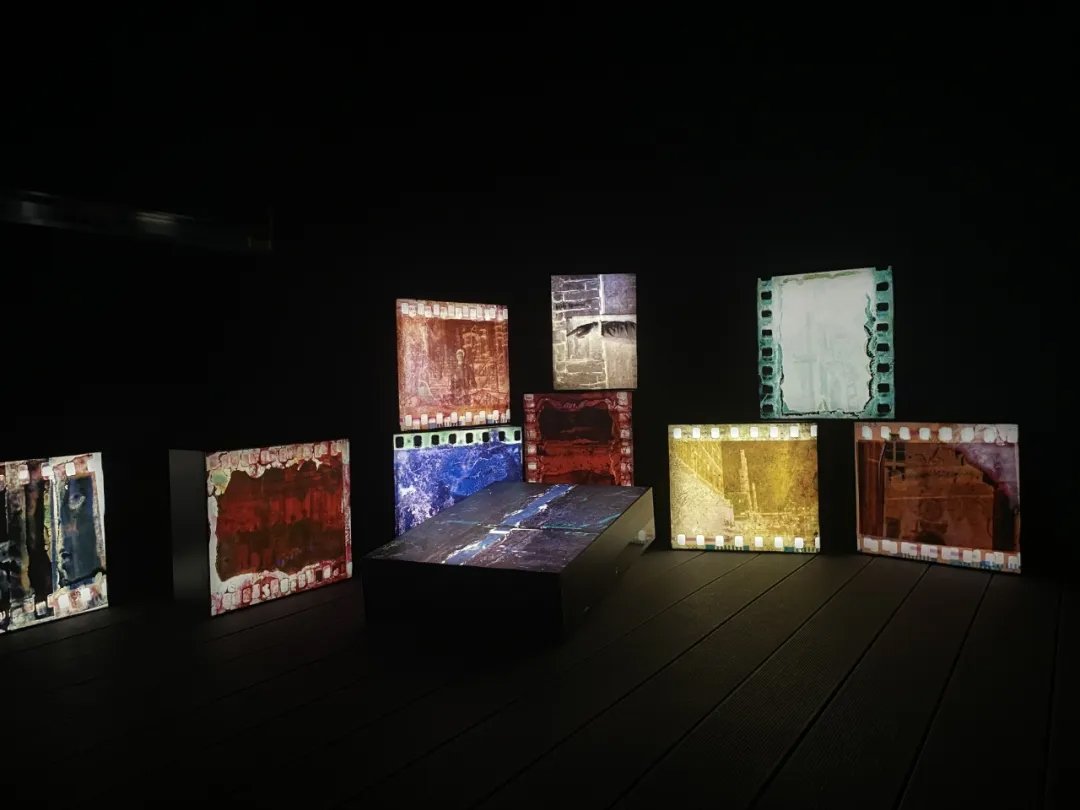

The exhibition, titled “Fossil Sunlight, Sedimentary Body,” is Yu Miao’s answer. Since 2021, she and local artist Li Yong have formed a research team that has repeatedly wandered through the open-pit mines, tailings, and factory ruins of Fushun, and delving into new energy projects such as photovoltaic fields, large-scale pumped storage power stations, and waste incinerations. In the continuous course of their journey, and in their multifaceted view of Fushun, the artists unexpectedly encounter many “sediments” on the surface and in the strata of Fushun: amber associated with coal, weathered films, drawings documenting factory subsidence, poems and letters of the workers… They emerge between the alternation of the old and new worlds, like a kind of nostalgia or a stubborn, indelible trace.

Also presented in the exhibition is another 9-minute short film by Yu Miao, titled “Amber.” Compared to the striking industrial style and poetic narrative of “Emu Universe,” this short piece is more grounded. It expresses how, after the decline in the value of resource extraction, people survive and cope in abandoned places. In an exhibition that rejects anthropocentric perspectives, what this work reveals may be the artist’s own respect and warmth for the truth of life.

The two short films may perhaps be seen as Yu’s return to her identity as a video art creator after six years, as well as her return to the Northeast after many years of wandering and doubt. However, the medium of this return is not her hometown, Shenyang, but the “influential” Fushun.

But facing the cruelty and immense reality revealed by Fushun, Yu’s expression is fully self-conscious, individual, and poetic. Her view and retelling of Fushun’s industrial trauma are emotionally charged but also go beyond criticism. In a sense, she has reshaped the expression of this exhibition, which originally could have been more profound and intense, in her own way.

Yu says that when facing the Northeast, she still can’t pass this “emotional barrier.” She must mobilize her emotions and invest herself physically. If she remains detached and restrained, it would be cruel violence against the Northeast. Thus came the language of Fushun we see created by Yu. From the perspective of those who do not seek grandeur or resort to rationality, this rough, barbaric post-industrial landscape is condensed into the smallest but also the longest emotional unit on the artistic level.

Yu Miao’s self-narrative is as follows.

Settling Down

The creative process itself is a rugged path, and we didn’t get here all at once. The two short films are far from enough to tell the story of our journey through Fushun over the past three years. Regardless, there are still many stories and feelings beyond the images that are like a lump in the throat, unable to be expressed one by one. On one hand, I feel that the works of artist seems unable to fully convey the complexity of Fushun’s current situation, but on the other hand, I strongly believe that the power of art can transcend mere factual means. As an artist, I cannot provide any political or economic solutions. All I can do is highlight and present these moments in a literary and artistic way.

Some may say that romanticizing the portrayal and expression might make the trauma and pain of this land seem too light, but as Mother Earth Emu says in the film, “You have been strong for a hundred years.” This kind of strength refers to the hardness of the past, when humans used machines for mining fiercely, but the relationship between humans and nature can actually be soft. This work carries a certain poetic tone of healing, and the compassion and hope conveyed at the end ultimately reflect my emotional connection to Northeast China.

I think if someone else were to make this piece of work, it might be more detached, but facing my first film related to the Northeast in my life, I cannot restrain myself. What I hope for is certainly for this place to become light and free. However, from the Russian railway construction and Japanese colonial mining of the early 20th century to socialist industrial and agricultural construction, the natural history of Northeast China is almost a history of technological transformation by humans through various top-down approaches. As a curator and artist, I am certainly interested in how to release the historical potential of the Northeast in the 20th century, but it must also be from a personal, bottom-up perspective, with healing energy.

As a person from the Northeast, facing the pain of my homeland, my first impulse is to settle it down rather than preach about it like a scholar. I cannot easily or academically explore the past of Northeast China; this is a barrier I cannot overcome. To pass this barricade, one must first acknowledge their identity, settle their emotions, and even confront the hidden pains within their heart.

Going to Fushun

Looking back at my relationship with the Northeast, when I was young, I definitely felt that the farther I ran, the better, just like all the kids from the Northeast did. I ran away when I was 18 and went to Canada, and it was through my interactions and collisions with others abroad that I realized the weakness of my roots. I envied the artists rooted in the global South or in Eastern Europe who had rich historical backgrounds and were good at finding artistic and academic starting points in their own contexts. I always felt that I couldn’t find my point because Northeast China had always been too vague for me.

Traditionally, the concept of Northeast China was first and foremost a very heterogeneous reference centred on Beijing and the Central Plains, whether in terms of climate, nature, or culture. It used to be loose and diversified, but after the railways came in, it was all stitched together. The Northeast has a history of only 100 years as a regional concept due to the space syntax derived from the railways. It is a relatively late development and a very general and even inappropriate concept created out of convenience for management and naming.

I didn’t start to walk the grounds of Northeast until quite late (probably in 2020). Before that, I had only skimmed the surface on a reading level without ever physically committing myself. But you know what? When I put myself into it physically, I suddenly realized its heterogeneity. Of course, as former crossroads of Asia, the history of Shenyang may be interesting, but when it comes to choosing an art project, it’s definitely going to Fushun. Fushun has a strong force, and it’s no longer just about people; it’s about flipping the earth directly. The power from the earth’s interior, the wildness of the factories, the original sites of energy and resource extraction, the relationship between human bodies and the earth—all of this is immensely rich and profoundly shocking. So every time I go to Shenyang, I leave quickly and go straight to Fushun. Once I’m in Fushun, it feels as if time and space are completely different. There’s a slow, tangible feeling of the ground, which is not purely natural but artificial and technologically processed. There are no such things as purely natural Changbai Mountains or purely natural flowing waters, only meticulously edited tailingså and rivers that have been interfered with. This is the truth of our place of existence, the truth of our lives.

Ghosts

In the Northeast, what I feel is a pervasive, omnipresent ghostly sensation, behind which lies a colonial history that cannot be easily identified or eloquently spoken. This ghostly sensation can even be traced back to my childhood. My family lived in the Ping District of Shenyang, which used to be a dependent area of the South Manchurian Railways, with houses built by the Japanese. The experience of living in these Japanese-style buildings is very different from Ban Yu’s descriptions of the Tiexi District. From a spatial perspective, the floors of Japanese-style buildings usually have a one-meter hollow space underneath. Because the buildings were old and in a neglected state, there were always a lot of rats inside, making frightening rustling sounds, and often giving me nightmares. Later the houses were demolished, and I didn’t go back because I couldn’t wait to leave that dilapidated place. My dad came back and told me that when the bulldozer pulled up the floors, that one-meter crawl space was exposed, and he saw my lost socks, the leg of a cloth doll, and remnants left by the Japanese who had once lived there.

It seems that in the years that followed, that one-meter crawl space has always chased me like a ghost, with a constantly accumulating sensation and gradually becoming a history that is difficult to describe but always present. The high school I attended was also a school built by the Japanese, and the lockers in the changing room of the swimming pool were left by the Japanese back then. One day, I suddenly noticed that someone had carved “Yoko and Nobita” on them with a small knife. Who were Yoko and Nobita? No one could tell you, but their traces always linger in that space.

Later, when I communicated with the group of northeastern artists, I found that many people had felt this ghostly sensation. The childhood fear comes from the buildings themselves and the invisible spaces within them, and it transforms into an artistic fantasy, but this fantasy ultimately becomes a symbolic existence: in fact, the socialist industrial construction we see, as well as everything that happened in Tiexi District and Fushun, were all built on the foundation of colonial modernity. The powerful entry of the Soviet Union, combined with our own development of socialism and worker productivity, piled up into a greater ghostly sensation that is inescapable and impossible to bypass.

Nearby

My exhibition is called “Sedimentary Body,” so what is “Sedimentary”? Most directly, it is presented in the Fushun No. 1 Oil Plant: those oil tanks and buildings were all brought by the Japanese, and the lives of workers in the 1980s and 1990s are another layer of sediment in this heterogeneous space. In the end, when the factory relocated, it took away the technical drawings but left behind these old buildings, oil tanks, photos and poems of its workers, films entangled with plants… This site has had a tremendous impact on Li Yong and me. The entanglement of time and history and the unrecognizable and unspeakable aspects of the Northeast seem to all be in this ruin. You have to throw yourself completely into it and feel its ghostliness in order to get past that unwritten, flattened Northeast, and re-study and discover an epic, three-dimensional Northeast.

As a North-easterner, I’ve spent my adult life building a global perspective by traveling around the world, so when I enter Fushun, even though it counts as my hometown, I still use a global-to-local methodology. This is why I designed a public event series called “Speaking Nearby: From Dongbei to the Worlds.” The concept of “Speaking Nearby” comes from the Vietnamese artist Zheng Minghe. She tried to shoot Vietnam but did not immediately point her camera at Vietnam. Instead, she went to Africa because she couldn’t face her hometown directly, and a place with a similar colonial background and experience in Africa provided her with a position of “Speaking Nearby.” I have a similar feeling. For example, I can’t point out the more closely connected and problematic parts of ecological connection and underground pollution here, so I pursued “Speaking Nearby” and looked for artists from former East Germany and former Soviet Union, who have experiences from the global South and in socialism, in order to connect Northeast China to the history of the global Rust Belt and the public trauma of former socialist countries and achieve the elimination of a single nostalgic and staring stance.

When looking at the Northeast systematically, you’ll find that the fate of this land isn’t a one-way linear movement but rather a cycle, one that also points to the operation of larger spatial relations. For instance, we see the immense uncertainty of fate hovering over the Northeast, along with the unpredictability of the forces behind it. This land was once so vibrant, almost instantly catapulting into the forefront of modernity, and its decline was just as rapid. Meanwhile, the shadow of the Northeast’s failure accompanies the rise of Eastern capitalism. But what about tomorrow? We can’t envision the future of the Northeast, much like we can’t predict the future of any other city. Who will be the next Northeast?

Forest

If viewed from a non-anthropocentric perspective, the decline of humans, to some extent, signifies the march of nature. The expressiveness of this film may still be limited because some wonderfully touching parts were left out. The oil refinery in the footage, which appears extremely desolated, was actually a vast forest just a year ago. Over the past decade or so, this abandoned factory has become wrapped in plants, with many birds nesting within, making nests out of branches, steel bars, and concrete. Perhaps they thought this would be their eternal home.

Li Yong and I once entered a huge oil tank enveloped by the forest, and we sang inside it. The echo of the sound, and even the space itself, gave us a tremendous shock. A psychic who lived nearby picked up many small shrines from the factory ruins and placed them in her home. Animals, people, and gods all seem so at ease at the edge of the forest.

But what is hard to imagine is that on the first day of our official filming, the entire forest in the oil refinery area was about to be cut down because the equipment in the factory buildings needed to be depreciated and sold as scrap iron—clearly, a very dominant logic had entered, and so everything changed once again. The logging was temporarily halted for a few months due to local heritage conservation opposition, and at the same time, global steel prices experienced a sharp decline. However, nothing ultimately changed, and when we returned in February of this year, it was already an empty wasteland.

In fact, due to subsidence caused by excessive mining, the land couldn’t be used for further development, which means that after the equipment is sold off, this place will become a wasteland again. The disappearance of the forest always evokes a sense of sadness; one always feels there could be a better way. But it is somewhat comforting that we can perhaps imagine that in another ten years, the forest will grow back in self-restoration. This is the part that goes without saying, the to-and-fro cycle where nature returns when humans retreat.

Chosen

Leaving the Northeast at the age of 18, after the long journey of global travels, I returned to the Northeast in mid-life, but why now, and why in this way? It might sound crazy, but I feel like I was chosen for this. Here, being chosen isn’t just about a relative match in abilities; it’s more about a judgment from the perspective of destiny. Standing by the edge of the mine pit, with the sun setting in the distance and a train thundering by, I strongly sensed the curse and sadness from the fossil fuel, as if an overturning force were pushing me to go back and choose to do this. In this process, it doesn’t really matter whether you make a video, become an artist, or make any benefits from the work. Returning repeatedly and wandering in the bitter cold, despite the difficulties, may be driven by a kind of obsession: not wanting to disappoint the inexplicable but chosen force.

During the pandemic, when I couldn’t travel but still desired to escape from Beijing, I realized that returning to the borderland might be a choice. Initially, I was still approaching it with a curatorial mindset, such as organizing and leading artists to explore the Northeast and inspiring them to create works. In the summer of 2021, sponsored by the Swiss Cultural Foundation, I once again led a group of artists with interests in technology and Southern themes to Fushun. But that one time was particularly frustrating for me. As a curator, I hope artists can crack open the scene or form a record, but when we arrived, everyone felt the scenes were too shocking, too good, but at the same time, too vast to grasp. Additionally, they all had other projects in hand, and after the visits were over, no one returned. In the end, I was the only one who returned to Fushun. So when I had the opportunity for this exhibition, I said, “Let me do it.” Thinking back, it was probably this urge to repeatedly return to the scene and the impulse to make this happen that made me feel like I might have been chosen by some kind of force.

In this project, the position of my role seems not to be that of an artist, but rather that of an initiator. I bring in external worlds and resources, while Li Yong helps me access the hidden corners of Fushun. Also instrumental in our filming was a friend of Li Yong from within the system, who said that his life is what it is, but he hoped to open up all the possible resources to us so that we could create what we wanted to express. These experiences really shattered my stereotypical impressions of the Northeast; beneath their toughness lies a very gentle part, presenting a very different northeastern characteristic.

This is also why I don’t want to work in the way of short-term residencies or extractive approaches where you come, take what you need, and leave. I don’t quite agree with the way artists in the art system treat the Northeast: coming to this warm, welcoming land, organizing the locals, but not telling them they’re here to film works, then leaving afterwards with their works and achieving their so-called careers. This is another form of exploitation, using the Northeast as a supplier of raw materials for images. My approach is to keep going back, to establish ecological relationships with the locals, and to reciprocate in my own way.

Underestimation

My de-anthropocentric concept was further reinforced during the pandemic. People used to enjoy talking about concepts like the Anthropocene, but the pandemic raised questions about the relationship between humans and nature. It was when I was physically trapped that I started to have strong questions about “what else could be done in the Anthropocene.” As a Western-derived theoretical framework as well as an indigenous concept infused with a lot of South American experience, how can we open up a local Anthropocene based on Chinese experiences? We cannot simply rely on translation or submissive learning and appropriation; more importantly, we need to inject our own experiences to transform and diversify them. This awareness has been cultivated over my years of working and studying in the West.

In the past year, I shared my walking experiences in Fushun worldwide and confirmed my thoughts above. Sometimes I am quite surprised that such a Northeast issue has received so much global response after only a few small attempts so far. Last autumn, I suddenly received an invitation from a research institution at University College London called the “Socialist Anthropocene.” They noticed my work online and invited me to London to give a lecture. The starting point of this institution is that socialist construction has caused destruction to nature, but at the same time, socialism also has its own experiences in ecological protection; it’s a multi-layered concept. However, their previous experience mainly came from artists and researchers from Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, and Central Asia, and they particularly lacked sharings of scenes from China. That sharing made me realize how little scholars from Eastern Europe and former socialist countries knew about China, and the world knew almost nothing about the Northeast.

This autumn, I am invited to visit and exchange with a series of universities and art institutions in North America, based on people’s enthusiasm for vivid narratives from China, especially the Northeast. The experience of the Northeast is so unknown yet so duly noted and welcomed, which I did not anticipate.

I think perhaps we have underestimated the Northeast before and really underestimated its historical energy. As the first and largest base of petroleum and fossil energy in Asia, once it breaks free from the framework of ethnicity and nationality and enters the Asian perspective as well as the network of relations of former socialist countries globally, its presence becomes very strong immediately, releasing tremendous energy. Therefore, when we look at the Northeast, going back to the trauma of the 1990s is not the only way for us to discover its uniqueness, and we shouldn’t think that we can only understand the Northeast solely by speaking of the loss and regret of its decline. In fact, when you’re in Fushun, the source of resource extraction, seeing how the trauma of humans and that of the earth are intertwined, and witnessing how water, forests, and mines as part of nature are impacted by humans, it’s difficult for your inner self to be filled with just a sense of disappointment similar to that shown in “The Long Season.”

Fearless

I realized that whether it was the film “Pan Yuliang: A Journey to Silence” shot six years ago or the film works of Fushun now, I’ve thrown myself into them in a very personal way. I was quite fearless when I made these works, putting myself out there naked. Of course, doing so is also risky and often attracts criticism, saying there’s a romantic sense. But what I want to convey is this kind of extremely direct emotional impact. Just like when I was standing in a huge mine pit, facing such a powerful scene, if I were to remain calm and restrained, it would be a kind of violence. I meant to process this immensely unbearable pain in a sensitive, individual, and feminine way, because for me, this is the most real and precious experience.

I went abroad at the age of 18, and I got pregnant soon after returning to China many years later. I still had an ongoing PhD thesis at the time, but because I had twins all of a sudden, I couldn’t take a full-time job or write the thesis, and I continued to take care of my children for many years. In that situation, contemporary art sheltered me, providing me with a space to wander freely and allowing me to do some interesting projects. The collaborations with Karen Smith, Cai Yingqian, and the Guangdong Times Museum especially allowed my creative and curatorial energy to be released. I have received a lot of help from my female peers along the way, and at times when there is a lack of institutional protection, this support based on female friendship has become a pillar and a shield for me, which I am very grateful for. At the same time, I didn’t relax but carved out a small artistic path for myself while taking care of my children. Although it was winding and bumpy, in the end, I did what I wanted to do in my own way.

As I wandered through Fushun, my heart often surged with a strong sense of hidden pain and hope. I am more and more like a northerner. This is not a geographic “north,” but one with many layers of meanings, including the shamanic belief that all things have spirits, the unique dry, cold, and bright nature of the natural belt and its phenology, and also the sense of deprivation in terms of resources and geopolitical subjectivity. This is the North that I feel closer to, the passion I hope to rekindle walking into it after my escape, and the re-understanding of this land during this process.

I remember that when I first returned to China ten years ago, I went to the Northeast once to do a sharing at the failed bookstore in Shenyang. On the train back, the idea of being a homecoming youth took place in my mind. On one hand, I felt excited about this, but on the other hand, I had no idea what to do, how to do it, what I should grasp as a starting point, or what is my identity is. I had a huge sense of confusion. At that moment, I couldn’t help but cry. Later, this sense of confusion recurred repeatedly, when I organized artists to the Northeast several times but ended up with nothing, when I expected contemporary art to produce research-based creations around northeastern issues but didn’t see the expected results…

Then I realized that it doesn’t matter if there is no platform, I can turn myself into an institution, it’s okay if I don’t have that many peers, I can go filming and generate discourse by myself.

Thus came these films and the exhibition in cooperation with the Goethe-Institut. On the day of the opening, I felt particularly emotional. From filming to the opening, over two months had passed, and I worked so intensively that I had missed the entire spring. Once the exhibition opened, my winter finally came to an end, and the heaviness that had accumulated in me over the past three years was finally lifted. I transformed the heavy burden of the earth and of deep personal emotions into exhibitions and films and presented them to the public, triggering a public discussion. All the feedback injected new energy into me, which made me feel incredibly relaxed. How the art world judges me is not important; what matters is that over the past three years, I have stood on tailings and delved into mine pits again and again, entered the construction sites of pumped storage power stations, and ventured into the sites of waste incinerations. I have seen both the curse of fossil fuels and the future of sustainable energy. I have rubbed against the earth of Northeast China with my own body, developed a deep understanding of the people of my hometown, and gained valuable awareness of issues. This process has profoundly transformed me, and I have finally become a daughter of the North.