Sitting across from Wang Xingwei, it’s hard to lose focus. Such concentrated attention is usually due to his unique way of speaking: his accent is distinctive, and his muffled pronunciation and slow pace of speech often collide with his hyperactive mind, causing his sentences and words to lose boundaries or blur together like a quantum entanglement.

This turned our interview with Wang Xingwei into more of a long stroll: slow, unfocused, and the opposite of efficiency, but at the same time free, relaxed, and unintentionally arriving at unforeseen truths.

Wang may have given this interview some thought before accepting it. Instead of starting with his works and exhibitions, discussing his identity as an artist and his regional background might have seemed unfamiliar and confusing to him. After all, he is more accustomed to talking about his own paintings and creations in a more specific and detailed manner than going beyond his own experience to summarize and discuss some kind of coexistence between people and geographic territories.

During the interview, Wang made no secret of his stance: he has no intention of engaging in a rediscussion of a northeastern nature that has long been concluded, documented, and defined, nor does he want to attach his artistic language to a particular territorial branch. He was delighted to emphasize and implement absolute individualism—and how this individuality influenced his life choices and artistic paths—rather than some conspicuous collective outcome.

We could even say that it is his absolute belief in self-subjectivity and his rejection of certain times and local mainstreams that have made Wang’s art journey “smooth” and “fortunate”: participating in art exhibitions, winning awards, and gaining recognition right after graduating from junior college; living in a small town in Northeast China in the early stages of his artistic creation, but never far from the actual scenes of contemporary art, and even becoming a local legend at one point; whether it’s leaving the Northeast for Shanghai later on or leaving Shanghai for Beijing, every step he took seemed to have paid off in the realm of art… Wang says he is willing to measure the world from the corner of his eye, to observe ambiguously like a spectator, without making value judgments, and to remain as vague as possible. It would be quite nice to try to be the lone hero of the age, if possible.

Wang presents us with an atypical sample of the Northeast. Whether he is situated in the Northeast or far away, he practices a true sense of inner artistic behavior—between the four walls, between me and myself, he shouts out “Objection” to existing narratives of Northeast China in an uncategorizable and irreplaceable manner. Although this may not be a strategic move, Wang expresses his resistance and reinterpretation of traditional northeastern traits through his logic of both life and art.

Wang Xingwei’s self-narrative is as follows:

Heading to Haicheng

My perception of my northeastern identity varies over time. My experience is relatively unique among northeastern artists. I did not leave during my school years like some, nor did I enter the art academy system like the older generation of artists who stayed. The first half of my artistic journey was completed in the Northeast. By the time I left, I was a grown man, married, and with a child, and my artistic development had reached a relatively mature phase. In terms of generations, I also seem to be a bit difficult to categorize; my first solo exhibition in Beijing in the mid-1990s belongs neither to the preceding generation of the ’60s nor to the succeeding generation of the ’70s. In fact, I haven’t emphasized my northeastern identity or sought out northeastern characteristics in my creations ever since my first works. Perhaps the main reason was that at that time, the Northeast was neither a trend nor a new faction. It wasn’t until later, when a younger generation of northeastern artists, writers, and musicians emerged, that the concept of “the Northeast” gradually strengthened in the fields of art and literature.

Even though I didn’t leave Northeast China in the early stages of my art career, I did have the opportunity to do so. The first chance came in the early 1990s, when the Old Summer Palace art community was taking shape in Beijing. Some of my friends left Northeast China for Old Summer Palace right after graduation, which left me feeling uncertain. At that time, leaving meant two things for me: quitting the system and leaving the Northeast. After completing my normal education in Shenyang, I was assigned to teach middle school, which was a very stable job. Most of my classmates are still teaching middle school even to this day. At that time, it was very hard to imagine quitting a job to become an artist. When I did quit, however, my parents didn’t oppose too much, probably because by then they knew that I could give art lessons. I remember that I earned a little over 100 yuan a month as a teacher, but with just five or six students in an art class, each paying 20 yuan a month, I could earn almost as much as my teaching salary. It was like discovering an alternative source of income. From that point on, I realized that one could leave the system and become a free, independent artist, which was almost unimaginable in the past.

After my resignation, I went to Beijing for a visit. I tried to look up a friend in a village near the Old Summer Palace called Fuyuanmen, but I didn’t know exactly where he lived, so I randomly approached people who looked like artists and asked if they knew him. When that didn’t work out, I knocked on door after door. It was a pretty rough method, and I went through a lot of wrong doors. At that time, I truly thought about going to the Old Summer Palace and wrote to people about it since I had already resigned. I wanted to give it a try because the cost wasn’t too high and we were all quite poor. A friend of mine even divided his monthly expenses into 30 small blocks and put 10 yuan in each. We all struggled, but I wasn’t too afraid of the hardships, especially since I was young at the time and believed that the more difficulties there were, the more artistic it felt.

Then I met my current wife in Shenyang and married her shortly after. She is from Haicheng and was assigned back there after graduation. Suddenly, my life had another fork in the road: to go to Beijing or to follow my wife to Haicheng. Looking back, these were two entirely different choices—one was the capital and the other was a county town. Haicheng still kept heated Kang bed-stoves in the houses back then, and in winter everyone had to carry coal upstairs to heat them. It was one thing for me to bear the burdens of living in Beijing, but it was obviously impractical to have my wife quit her job and follow me, especially since she came from the countryside and it hadn’t been easy for her to go to a university. Asking her to give up her stable job for me was unreasonable. In the end, I decided to go to Haicheng instead of Beijing.

A Lone Hero

Generally in my life, the bigger the decision, the faster I tend to make it. For example, buying a house might have taken me less than half an hour to decide. A similarly quick decision was made when I wanted to move to Shanghai, I made the decision one month and was on my way the next. I didn’t hesitate about moving to Haicheng either, I just felt that as long as I had my own space and time, that would be enough.

I was in a very confident state and felt extremely positive at that time. Perhaps it had something to do with my experiences, how my first artwork after graduation was chosen for the Liaoning Art Exhibition and attracted the attention of many peers. I even felt a little upset about not making it to the national exhibition, but later the second artwork I made with Professor Gong Lilong was accepted and made it to the cover of an art magazine. By 1993, I had won several awards in a row and received tens of thousands of yuan as prize money. As a result, my perception of myself was not necessarily objective, but rather very self-assured. So when I went to Haicheng, it didn’t feel like I was going to a new place or moving from a big city to a county town.

Similarly, I wasn’t concerned that leaving Beijing for Haicheng would distance me from the heart of the art world. At that time, the main sources of information were still art magazines like “Jiangsu Art Monthly” and “Art News of China.” There weren’t many exhibitions, and only a few contemporary art exhibitions were held each year, even in Beijing. I could still go to Beijing occasionally to show my artwork, so I wasn’t too worried about the artistic atmosphere.

I still doubt that I would have really settled for Old Summer Palace even if I hadn’t gone to Haicheng, because I don’t like to cluster in a crowd. For many painters, the idea of a bunch of arty youths hanging out all day, drinking and bragging, might sound very appealing, yet I couldn’t accept a life that only appears artistic but is actually filled with dull, ordinary creations. I’d rather lead a non-artistic life, but have my work stand the test of time. So I began to wonder: Could I be a lone hero? Could I independently take on the identity of an artist and walk that path? Of course, I was young and had no fear of authorities. Winning awards, making money, and gaining recognition, things that many aspiring artists dream of all came to me quite easily, and I felt like I hadn’t even started yet. Why was it so easy? I was very confident and didn’t care where I went—even if it’s the countryside, there was nothing to fear.

Looking back now, I was very fortunate to be able to leave the system and stay in the Northeast to pursue art in the 1990s, when stability was very much in demand in Northeast China. The people I met along the way were relatively open-minded, supportive, and allowed me to explore what I wanted. So far, I have always been sure that art is what I want to practice and the life I want to lead. That has never changed.

Sure, there were many objective differences moving from Shenyang to Haicheng, such as leaving behind family and friends and the lack of contemporary art communication. Nevertheless, I wasn’t lonely. I lived with my wife in the teachers’ residence, and because our apartment was on the first floor, I could often hear my wife’s two colleagues discussing me as they dug wild vegetables outside our window. They called me “that guy” who stayed home all day and said I was a painter but didn’t paint anything worthwhile. I heard them, but I wasn’t offended because I understood why they said it. To them, an artist without a real job was like a homeless drifter. If someone lost a bicycle, they would immediately suspect me.

A Blind Confidence

Although I seemed to be in a relatively marginalized state in Haicheng, that didn’t stop me from possessing a blind, fanatical confidence. For example, in 1994, I approached Mr. Gu Zhenqing about a group exhibition in Beijing and asked him if he could help us pay the expenses, even though we hadn’t even started painting yet. He agreed, and that’s how the first group exhibition in Beijing was held at CAFA Gallery in 1994. Speaking of which, the affirmation and recognition I received in the early stages of my art career seemed to have little direct relevance to the physical space in which I was located but rather resonated beyond Haicheng, Shenyang, and even the Northeast, to the seemingly more distant Beijing, the center of contemporary art.

In 1993, “My Wonderful Life” participated in an exhibition in Liaoning. I paid the entry fee, and all the other works were juried normally; only mine was excluded. I was particularly furious about this incident, which was a turning point for me. It made me realize that the Northeast was an existing path for artistic practice, and the first two steps I took were enough (leaving the system and participating in exhibitions). There was no need to continue adapting to the standards at that level. Since the local environment no longer provided enough growing space, I needed to gain advantages and success on a bigger stage.

You could say that although I stayed in the Northeast, my evaluation standard of art, my self-awareness, and even my view of contemporary art no longer remained limited to that region. In fact, ever since the first time I bought “Jiangsu Art Monthly” from a newsstand in high school and learned about the ’85 Movement, I have never narrowed my artistic domain to the Northeast. When I studied painting during my three years of high school, I kept up with, observed, and judged the development of contemporary Chinese art from 1985 to 1989. Although I was only in my teens, looking back, my understanding of contemporary Chinese art then was not much different from today. I clearly knew what was the best at that time, and that “best” has indeed stood the test of time. This made me even more confident: I hadn’t misjudged.

My sense of certainty was strange. Like when I submitted my first artwork, I knew I was going to win, and I did. Such a coincidence seemed very subjective and overly idealistic, without any supporting evidence. In the end, it could only be explained as my personal blind confidence.

Perhaps it was this blind confidence, plus the relatively marginal geographical location, that shaped my subtle sensitivity toward the so-called center, trends, and classics during the early stages of my creations. Of course, it also implied a certain attitude of mine; I did not fully approve of the art creations in the 1990s. They represented a downfall from the original philosophical sublime to the banter and mockery of post-realism. For example, I appropriated those successful artists in “Standard Expressions After ’89” and later interpreted this act as my jealousy towards them, because when I first came to Beijing from Northeast China, I realized that those artists were already in the spotlight, representing Chinese art on the world stage. They had taken another step forward, and at that moment I had to think: What is my identity in Beijing? What is our identity as we move towards the world? Are we spring rolls or what? Are our faces the performance faces, or are they faces exploited by others? This appropriation here is not necessarily meant to form criticism, much less tribute; instead, it relies more upon a collection of phenomena to achieve a deconstruction or a new interpretation.

Looking back now, I find my creative stance quite sensitive and intriguing at the time. What’s even more interesting is that I didn’t actually see the original works of Fang Lijun and the group until much later, and they felt very different from how I first perceived them through magazines or other media. It seems that the true message of the painting can only be fully revealed through the original copy. Of course, if I had seen the originals from the beginning, I might not have reacted in the same way and would have lost that impulsive urge to respond to them. If you look at it this way, it was somewhat accidental how my batch of work was completed and stood its ground back then. If I hadn’t misunderstood Fang Lijun and the others, I probably wouldn’t have become the person I was later on.

A Legend

As we entered the new century, just when everyone thought I would stay in the Northeast for good, I finally left and went to Shanghai. From the strategic perspective of creating a legend, it would have been feasible to stay in the Northeast, and the longer I stayed, the more of a legend it would become. However, building a legend is not the whole story after all, and at best it serves as a component in the choosing process. Some things are like that; once you see them as the centerpiece, you’ll be abducted by them and lose your own ego. Therefore, whether I stayed in the Northeast or left is rather random. In fact, it is not even a self-centered decision, as there are many factors involved. Besides art, there is also life, and apart from myself, there are family members, my child, and so on. At first, I used to love telling people that it was for the education of my child when they asked me about Shanghai, but that’s definitely not the sole factor. It’s a combination of various reasons and is difficult to explain.

Perhaps, in the eyes of many, my first choice should have been Beijing since I was leaving the Northeast. First, there was the missed opportunity of the Old Summer Palace, and second, Beijing was still more diversified and active in terms of art development. But I went to Shanghai anyway, not knowing if I had done the right thing. When I first arrived in Shanghai, some of my friends already believed that I had made the wrong choice, but I don’t see it that way. Be it Beijing or Shanghai, it’s just a matter of choice that leads to different results. I later achieved another artistic transformation in Shanghai, but I can’t claim that it’s better than going to Beijing because that’s a road I never took. All I can say is that the years I spent in Shanghai were very free and happy, and I opened myself up to more communication and socialization. I’ve never been fond of living in a crowd, but in Shanghai, ever since I set foot in the M50 Creative Park, I’ve started to live in a public communal group. I made some changes half-heartedly, like going from painting in hiding to being able to work with the door wide open, where anyone can drop by and have a little chat, which is the complete opposite of how I used to be.

During the years in Shanghai, my creations reached a stage where paintings merged with other art forms. Paintings, films, performances and installations often appeared together in the same group exhibition. The pursuit of artistic value was not about perfection in production and visualization, but emphasized more on conceptual expression and the pursuit of expressiveness and impact. At that time, painting was no longer the mainstream medium of contemporary art; it retreated to a position equal to other art forms, and even had a certain conservative disadvantage. Painting was undergoing some changes during this era, sacrificing some of its commodity attributes and striking a balance among artistic medium powers through self-depreciation of commercial value and self-damage to its own perfection.

That was my Shanghai phase. Looking at my work from back then, I no longer pursued “well-painted” creations, nor did I place much emphasis on their commodity or investment value. But it was a necessary phase because it was a proposition for painting demanded by the times. In an exhibition, if your works were merely stylistically perfect but lacked novel expressions, you would fail to remain in the same space and interact with the artists of your generation. Of course, in the long run, the absence of interaction doesn’t mean that the artwork is meaningless, and it will certainly gain significance on another level of narrative. But if everyone remains elitist and focuses only on the quality of the paintings, then they will collectively lose their voice in the face of this era.

Silent and Deserted

Many of my perceptions of Northeast China are quite subjective and personal and seem less relevant to the major trends. Sometimes, my personal feelings are disconnected and detached from the times and collective emotions. The well-known Northeast Renaissance, for example, and the job displacement wave of the 1990s, repeatedly written about by authors like Ban Yu, didn’t leave a significant impression on my memory. I lacked the intense mutual empathy because both my parents worked in a hat factory, which shielded me from experiencing the dramatic twists of fate that befell the typical working class in Tiexi District. Especially with my father retiring early and starting his own transport business, my life wasn’t directly involved in the monumental changes of the era. Nevertheless, I recall perceptible traces in the surroundings. My most vivid memory is the sense of bewilderment among those who lost their jobs. Workers were unaccustomed to business dealings because it was difficult to let go of their former factory pride and habits, and they struggled clumsily to adapt. If you go to Zhongjie, you’ll see a bunch of people selling slippers in rows of carts and stands. How can you make any money when everyone is selling slippers? But there seems to be no other way, and slippers are cheap with low costs. You may not earn much, but you won’t have a lot to lose either.

Come to think of it, the rapid development of the Wuai Market in Shenyang during the 1990s was somewhat related to the mass layoffs of workers. People were forced into the market, stocking goods from the south and learning how to trade. However, only a few managed to make money; most ended up losing because the business environment in Shenyang was relatively weak, and the habits of the people there were not quite in tune with the principles of doing business. Unlike people from the South, who understood the importance of keeping promises in business, former northeastern workers had never had a life revolving around standards of profit. Their commitments were more rooted in social interactions, and calculating gains was seen as a moral flaw. They believed in and relied on broader commitments, such as those guaranteed by the state. When facing such a grand context, individual efforts and desires for survival seemed insignificant.

I’m not particularly sensitive to urban spaces and architecture. While Shenyang had some Soviet and Japanese-style buildings, they never evoked any strong feelings in me. Instead, what left a lasting impression in my mind was the scent. When I was young, I lived on a farm in the suburbs, and every time I went to Shenyang, I could always catch the smell of rust in the air and water. I could see waste slags from steel-making left on the streets, and that was my earliest, most unforgettable impression of Shenyang as a city of heavy industry. Another moment etched in my memory is that one time in middle school when I had to go home to fetch something. As I walked back to the school gate, the streets were almost deserted. It was all very quiet, bathed in sunlight, with the smell of burned coal lingering in the air. That moment encapsulated my impression of Shenyang: silent and deserted.

If you were to ask whether I feel a sense of belonging to Northeast China or Shenyang emotionally, I’d say it’s more of a recognition. Of course, not all North-easterners feel this way; for many, leaving is a result of the harm inflicted by the place. I consider myself very fortunate to have encountered open-minded parents and great teachers. My sense of belonging to Northeast China is based on experiences free of harm. However, I have also left, and I gradually feel that I can never go back. Everything has changed, including the place, its people, and myself, making it impossible to retrieve the original feeling. Therefore, I don’t have that nostalgic desire to go home like most middle-aged people do. Some believe in the saying “returning to one’s roots,” but for me, although I may not stay in Beijing and don’t know where I will end up eventually, I definitely won’t and can’t go back to the beginning. This reluctance isn’t driven by fear but rather by a desire not to rebuild certain connections. When the people in those relationships are no longer who they used to be, you’ll come to realize that everything you face is an illusion.

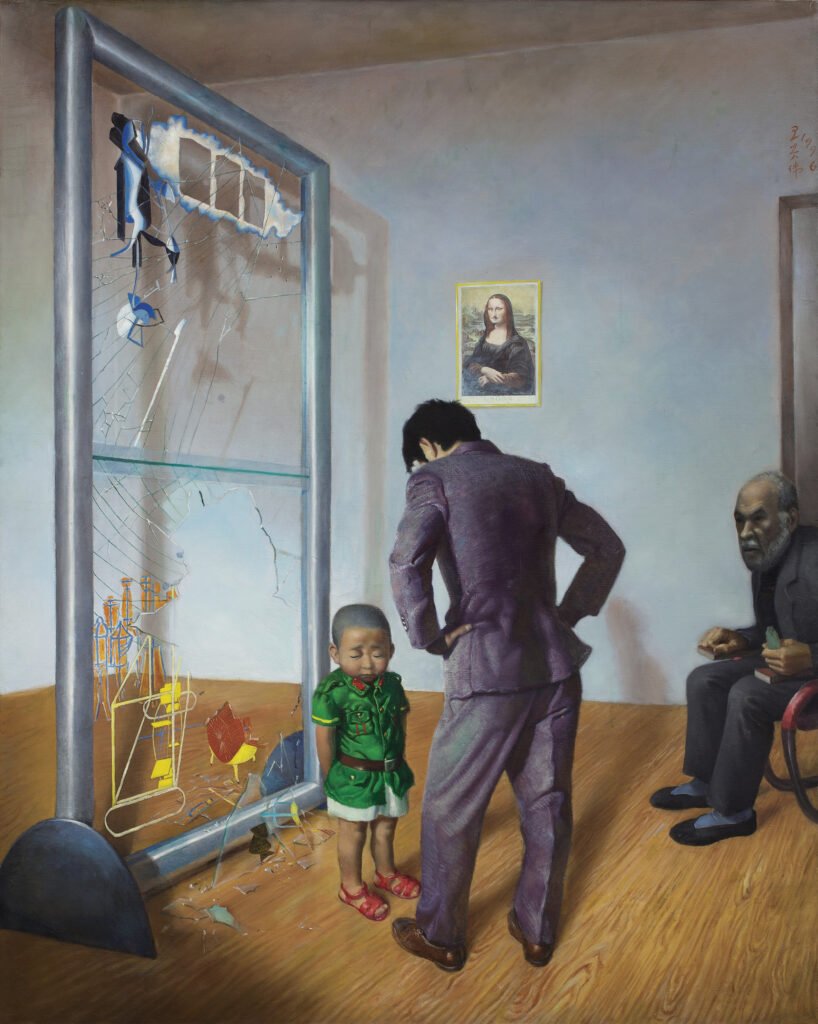

Of course, the premise for not returning to Northeast China is that my artistic creation is not based on absolute locality. People are actually easily separated from most of their identities, roles, and relationships. Most artists are capable of working detached from the location of their source materials. However, this detachment does not mean that my language fails to capture a shared vision of the era or the region. In fact, my grasp of commonality is completely faithful to specific realities. For example, my depictions of young couples and family life are drawn from my own marriage and family members, while the layout of the room and the furniture were all based on the actual settings of my house in Shenyang and Haicheng. Commonality also has its “windows,” a period where everything possesses both strong individuality and strong commonality at the same time. If you miss this window period, then the individual will remain individual, and you will only obtain false commonality even if you attempt to summarize it.

Artistic expression always lags behind. The tremendous changes that Northeast China experienced in the 1990s didn’t find their way into literature or film narratives until many years later. What Shen Xuetao and Ban Yu wrote were really the stories of their fathers. After seeing Wang Bing’s “Tiexi District,” I was struck by the brutal reality it portrayed, but I also wondered: Why couldn’t people relate deeply to the sufferings when immersed in such cruelty? Maybe it’s the nature of the camera or the nature of the person. The truth is, at that point, there is no time for sentiment or regret for a devastated group. They have to survive first, either by selling slippers or through other means of labor. There’s no time to complain, let alone reflect. The shattered narratives prevalent in later retellings seemed equally tenuous to me at the time. When you’re living in a deprived state, you simply can’t resonate strongly with greater pains. What I saw was the reality I could see, and there was a certain distance between that reality and a particular emotion.

An Afterglow

I gazed at the era through its afterglow, trying to refrain from making value judgments and to keep a vague grasp on life. That’s why I still have my doubts about the Northeast Renaissance or about Northeast China turning into a theme itself. Is this really necessary for the daily life of the Northeast? Does Northeast China need to renovate itself by forming these themes? These repetitive discussions—are they a knowledge-producing mechanism, or just the absolute self-indulgence of theme creators themselves? In the 1990s, we often talked about “catching up,” hoping to keep up with the trends. However, to me, this attitude seemed to be a surrender to a dominant culture, which I don’t fully support. I don’t want to “curry their favor” because it means I must speculate about what is meaningful. On one hand, this speculation is quite a challenge, and on the other hand, once you start pleasing others, your own value diminishes. For me, the Northeast’s current role as a performer being watched and judged indicates a certain loss of dignity. Its naturalness and originality are somewhat alienated.

For artists, there remains a significant distinction between using the Northeast as a free inspiration source or as a pledge of allegiance. When considering the overall utilization of the Northeast, how to avoid descending into mere kitsch and brutal exploitation is a topic that needs to be confronted directly.

Since life itself has no conclusion, the works created by artists will always vary. Ban Yu’s Northeast, Zhao Benshan’s Northeast, and even the Northeast illustrated in “Country Love” and “Ma Dashuai” all tell completely different tales. What people describe is always the spirit of the times that they can experience and touch. To me, the narrative reality of art springs from concrete life experiences rather than macro-regional concepts. For instance, the television and wardrobe shown in my works were the same ones I had at home. Here, the family space replaces geographical concepts and becomes the primary stage of creation.

Society has its own history, artists have theirs, and my personal history carries its own inertia and frameworks that are yet to be discovered. However, an individual’s history may not ascend in parallel with the historical rise of the times. Likewise, the decline of the era doesn’t necessarily reflect directly in my language. Not all artists have to be synchronized with the mainstream of their times. Some creative logic simply doesn’t align with the rhythm of the grand era and needs to be cut off. For me, the strong determination to accomplish a particular idea cannot be ignored. Whether it can be sold at a good price, whether others recognize it, whether everything is improving—these are only relative, even distractions that need to be shielded.

The true triumph of art lies not in its present but in the transcendence of time. To achieve such transcendence, it ultimately requires the contingency of history and unconscious genius. Here, unconsciousness does not refer to whether a person can fulfill his own intentions, or whether he has excellent ideas or judgments; these are far from enough. What holds true value is the aspect of unconsciousness that only reveals itself in the future—something unstandardized, intuitive, natural, and non-utilitarian. Naturally, I hope to carry some of this unconscious genius with me. In fact, I’ve had occasional sparks of similar feelings in my past creations. The yellow shirt from “My Wonderful Life” and the child in military uniform from “Poor, Old Hamilton” were both unconscious choices initially, and the message they conveyed gradually built up over time. Neither I nor my audience took them too seriously back then, but after a while, their significance became clearer and more intriguing.